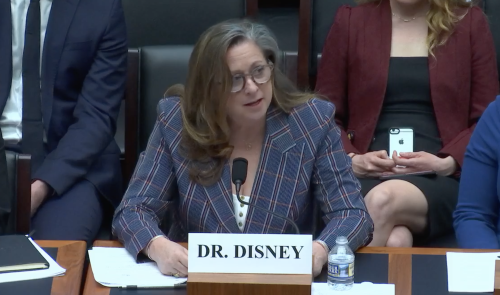

On Wednesday, May 15th, Patriotic Millionaire Abigail Disney appeared before the House Committee on Financial Services Subcommittee on Investor Protection, Entrepreneurship, and Capital Markets to testify on out-of-control executive compensation in corporate America. The hearing in full can be viewed HERE. Below is Abigail’s full written testimony.

Thank you Madame Chair Representative Carolyn Maloney for convening this hearing on Promoting Economic Growth: A Review of Proposals to Strengthen the Rights and Protections for workers. Thank you, as well, Chairwoman Maloney, Ranking Member Huizenga, and Members of the Subcommittee, for inviting me to testify. The subject we are here to discuss is critical to the future of our country.

I am here to help shed light on the problem of excessive executive compensation and the injustice of the contrast between that compensation and the low wages and poor conditions of those that work at the bottom of the pay scale. These problems have been growing over the decades and will continue to worsen, and have deeply negative consequences for our great nation.

My mission is to use the voice I have to speak for those whose voices would otherwise not be heard. I hope to enlighten and engage those in powerful positions and inspire them to make change—starting with this committee as well as representatives of various other companies and organizations.

I do not speak for my family but only for myself.

I have no role at the company, nor do I want one.

I hold no personal animus toward Bob Iger nor to anyone else at the Walt Disney Company.

I have repeatedly insisted, in fact, that he and the rest of management at Disney are brilliant and that performance-based compensation for them is totally appropriate.

The questions I am raising are simply “is there such a thing as too much?” “Does what a CEO gets paid have any relationship to how much his janitors and wait staff and hotel workers are paid?” And, “Do the people who spend a lifetime at the lowest end of the wage spectrum deserve what they get, or does every person who works full-time deserve a living wage?”

I know a little something about the dynamics of money. It is a lot like the dynamics of addiction.

Alcohol, like money, can be a harsh and demanding task master; once one glass of wine becomes normal, it demands a second, and then a third. Returns diminish, and more is always, eternally required. That is why billionaires leave terrible tips, heirs rankle at the idea of estate taxes, and wealthy old men go to their graves grasping for yet more. (Does the name “Rosebud” ring a bell?)

I believe that there is such a thing as too much money. And, to be yet more heretical, I believe it is possible to say no to more.

As an heiress with a famous last name I’ve been granted a free pass into the places where wealth is unapologetically flaunted. I’ve watched as, over the last few decades, the wealthy have steadily self-segregated into ever more restrictive and lavish spaces. In those spaces, even as they discuss the scourge of poverty, they guarantee that they will never have to look a gross inequity in the eye. In so shielding themselves, they have lost the ability to tolerate discomfort, and so work ever harder to keep their delicate sensibilities out of harm’s way.

I’ve seen what excess looks like in the form of the private planes parked chock a block at posh conferences about global warming, where no one so much as nods at the grotesque irony of such a thing.

I’ve lain in the unnecessary queen size bed of a 737 big enough to carry hundreds but designed to accommodate no more than a dozen.

I have seen it in 85 million-dollar mansions dotting the Hamptons—empty— I have watched children decked out in designer outfits expensive enough to fund a whole family’s healthcare for a year and I’ve been a guest in homes with toilets that clean your backside on your behalf. (Yes, there is such a thing, and yes, it’s really gross.)

It is time to pull back the curtain on this garish life and ask ourselves how high a handful should soar as the rest of us watch the American Dream collapse for a large majority of working people?

This is not just a question of what is moral or what is right. There’s an important economic case to be made for addressing inequality across the spectrum. In tolerating such extreme unfairness, we have begun to cannibalize the very people that make this economy thrive. After all, no middle class, no Disney.

And yes, low unemployment is great, unless the only jobs available are low-paying jobs with no benefits, no hope of retirement, no respect.

Offering education to employees is also great but sidesteps the issue at hand. You do not pay a worker for what they might or might not eventually do tomorrow. You pay them for the work they’ve done today. And you pay them fairly for it.

Calling this a “starter job” reveals a presumption of privilege that bears no relationship to the reality of most college graduates who do not have well-resourced parents with money to supplement their income, and who do not have the luxury of taking a job that will offer a wage dwarfed by the enormous debt they’ve incurred getting the education most of their parents got either almost or totally free of charge.

Philanthropy is often offered as the answer to the problem of inequality. While wonderful, philanthropy is not the answer because these problems are not a question of personal choices or individual behaviors. They are the consequences of structures that create and then enforce a deeply unfair and inequitable society.

Philanthropy offers a man a fish, even teaches a man to fish, but persistently fails to ask why the lake is running out of water, or why the man does not know how to do what his ancestors knew perfectly well how to do and did every day.

Philanthropy supports art and education and many indispensable cultural institutions, and we should all be grateful to the donors who take this job on. I do not question the generosity it entails.

Philanthropy that helps the poor is in many ways an even more admirable form of the art, because it offers benefits that the donor cannot possibly enjoy him or herself.

But in attempting to address the consequences of deeply unfair economic structures—the very structures, in fact, that make philanthropy possible—even the most generous charitable giving uses the master’s tools that can never dismantle the master’s house, to borrow a metaphor from Audre Lorde.

Even if philanthropy could face its fear of asking where all the money is coming from, it still cannot work at large enough of a scale or in enough unison to address the problems I am talking about. Even the largest philanthropy is dwarfed by government programs like Head Start, Food Stamps, Social Security and Medicare, each of which has proven effective and has already lifted many millions out of poverty.

At Disneyland in Anaheim, workers had to fight for years to get their minimum wage raised to $15/hour, all while the cost of living in Anaheim continued to rise. Studies show that today a living wage in Anaheim is closer to $24/hour. Studies show, in fact, that $15/hour is not a livable wage in most places in the US.

All this for the very people my parents and grandparents taught me to revere and treat with the utmost respect. The world of low wages and wondering where your next meal might be coming from is, after all, where my own grandparents got their start. I vividly remember my grandmother telling me about the many mornings she left for school in Kansas wondering how she would be able to feed her siblings when she got home. She left high school at 16 to support her family and worked damn hard to do that.

I can say with total certainty these are not the values my family taught me.

I have spoken up because I am uniquely placed. As an heir to Disney’s legacy and yes, no small share of its money, I feel a special responsibility to speak. As my life has brought me into relationship with many friends and colleagues who have been as unlucky at birth as I’ve been lucky, the contrast between their lives and my own is hard for me to bear.

I am also uniquely placed because I am not just any heir, and because Disney is not just any company. Disney is not US Steel. Nor is it Procter and Gamble, or Apple, or Chevrolet or any other iconic American brand. The Disney brand is an emotional one, a moral one, I would even say it is a brand that suggests love.

I have spoken up as a Disney about the Walt Disney Company not to pick a fight, but to put those moral undertones and all that love to constructive use. Because this is a moral issue. And it is so much bigger than just Disney. For too long the business community has brushed aside moral considerations as beneath them—naive, childlike, irrelevant. For too long it has been anathema in the business world to be tagged with the label of “do-gooder.”

And when I call out the problem presented by any man, however brilliant, walking away with 65 million dollars after only grudgingly offering his own employees a wage that cannot support a single person much less a family, I know it will get a lot of attention, and hopefully jar a lot of sleepwalkers into consciousness.

I spoke out about Disney in spite of the fact that I am well aware that Bob Iger is by far not the worst offender as far as excessive compensation goes, but because I want to bring attention to the issue of inequality more broadly and to shine a light on all that we have gradually allowed ourselves to become accustomed to in the name of this fundamentalist version of capitalism we currently practice.

It wasn’t always this way. It was made this way by people and therefore by people it can be changed.

This is, oddly enough, not an issue that divides red from blue. Not, at least, at the highest levels. Many an executive who calls himself liberal or donates to candidates whose rhetoric would seem to indicate a care for the poor, fails to bat an eye when offered his or her princely compensation.

Many of these men and women are perfectly nice people. But the hypocrisy has been so normalized I don’t think most of them even see it.

Disney itself is uniquely placed to lead us out of this quagmire if its management so choose. Disney led when it offered benefits to same sex partners. It led when it began to foreground environmental concerns in all of its divisions. It led when it began consciously to focus on the hiring and promotion of women, of people of color and other groups. On this issue, Disney could lead once more.

Disney, after its merger with Fox, will be the largest media entity the world has ever known.

All the company lacks to lead, ironically enough, is the imagination to do so.

I want to make it clear that I have raised all of these issues with Bob Iger in the past, quietly and politely and behind the scenes with decorum and deference. I was quickly and condescendingly brushed aside. A public position is the only choice I have left to try to influence this.

What could Disney do? It could raise the salary of its lowest paid workers to a living wage. There are plenty of economists who would be only too happy to help them figure out what that living wage is.

And when you cry out that they can’t make a profit while paying a living wage, keep in mind that right now the company has never been more profitable, and is paying record compensation out to management. I hope you’ll forgive me if that claim gets a cynical groan from me. This is merely a question of priorities.

Here are some more thoughts on what it is well within Disney’s power to do. Many of these are ideas given to me by people who work low wage jobs at Disneyland when I spoke to them last year.

Disney could take half of this year’s enormous executive bonuses, all of which are a fraction of revenues, and place them into a dedicated trust fund which could help workers with emergency needs like insulin, housing, transportation and child care.

Disney could rehabilitate moribund housing near its parks to ensure people do not have to drive three hours every day to get to work.

Disney could restore the employee stock option program for all employees, not just management.

Disney could restore the right that workers once had to get into the park for free, since as things now stand, they cannot afford to bring their own families to the happiest place on earth.

Disney could make food available to employees. Many employees currently survive on food stamps and yet are required to throw away huge amounts of food on the job. I cannot imagine how that feels.

Disney could hold two or three seats on the board for employee representatives, to be elected by their peers. They, being well versed on what’s going on the inside of the company, could probably contribute more effectively to board discussion than yet any CEO from an unrelated industry anyway.

Because the board is currently made up entirely of people who either are or hope one day to become CEO’s, it is hard to imagine any kind of compensation getting much push back.

Disney could, in the future, pay attention to the relationship of the CEO’s compensation to the wage of, not its median wage worker, but its lowest full-time worker.

This leads me to respectfully suggest that the Human Capital Disclosure Bill needs one tweak. On the whole the bill is important and worthy and should pass but here’s the thing. Pegging the ratio of the CEO’s compensation to that of the median worker is not a reliable metric. It does not reflect that in some sectors, like banking, median pay is much higher than in others.

That means that men like JP Morgan Chase Jamie Dimon are not getting called on the carpet for this problem even if they are just as guilty of driving their own workers’ wages down while walking away, year after year, with obscene amounts of money. They might in fact be even more culpable, since they’ve spent years as some of the primary architects of the very financial systems that have blithely encouraged the downward pressure on not just salaries, but benefits, vacations, parental and family leave, retirement benefits and more.

And while we are on the subject of Jamie Dimon, it is useful to remember how we all recently watched him struggle to answer a simple question Representative Porter posed to him about the entry level wage at JP Morgan Chase.

His demeanor in that moment was that of a man who’d never pondered the question before, nor worked with anyone with the temerity to ask him about it. While he floundered for an adequate response that would ultimately never come, he looked like a man bent on never acknowledging one very obvious and important fact: that in a year of record profits and 8 figure compensation at the highest levels, the pay at his bank is way out of whack and further, that if someone working full time for him cannot afford even the most basic necessities without running up a crushing amount of life-destroying debt, something needs changing, and fast.

There is nothing inherently wrong with an 8-figure payoff—unless there are people at the same company rationing their insulin. Then it is simply unacceptable. And the CEO has a moral obligation to know what life is like for the low wage workers under his own roof.

Comparing a CEO’s compensation with a median worker’s wage renders the experience of low wage workers invisible and implies that they are irrelevant to the well-being of the very company they labor to support. It implies that the fates of the CEO and his lowest wage worker are unconnected. It is this feeling of disconnection that enables management to repeatedly ignore conditions deteriorating right under their noses.

No CEO, no matter how brilliant, is any better or more important than a janitor. No one is too good to scrub a toilet. To leave the lowest paid full-time worker out of the equation is to imply that some people should be invisible and disregarded.

The work that needs doing is not all up to Disney and, again, Disney is a long way from being the worst company in this regard. Lest you doubt this, have a look at the fortune Jeff Immelt amassed while driving share prices down more than 30% during his tenure at General Electric.

We need to change the way we understand and practice capitalism. We need to put people ahead of profits once and for all. Yes, leadership has a fiduciary obligation to their shareholders. But they also have a legal and moral responsibility to deliver returns to shareholders without trampling on the dignity and rights of their employees and other stakeholders.

This moment has never been simply about excessive compensation. But outrageous payouts do get us thinking about business practices that are unsustainable, irresponsible and morally corrosive.

We need to change our assumptions. If you cannot afford to pay a living wage, you cannot afford to hire a worker. If you cannot afford to stop dumping chemicals into the river, you cannot afford to be in the chemical business. If you cannot afford to replace a key employee who has terrorized and harassed his peers, you cannot afford to have him there in the first place.

We need to change our metrics so that they better reflect our values. We need to look at the ratio of a CEO’s compensation to that of his lowest-paid, full-time worker, because that person is just as much a part of the company as the median paid worker and just as much a part of the company as the CEO. Let’s choose to tether their fates and make it more difficult to leave that low paid worker out of consideration when any important decisions get made.

It is time to say, “enough is enough.” It is time to bring a moral and ethical framework back to the way we discuss business. It is time for business leaders to recognize that they have altered the nature of this communal project we call the United States of America, and that now they must hold themselves accountable to their fellow citizens. And if not, then we must hold managements to account on citizens’ behalf.