Our criminal justice system is broken, and Attorney General Jeff Sessions and his pals in the private prison industry are making it worse.

Last year Sessions, believing the Obama-era DOJ had been too lenient on offenders, ordered federal prosecutors to pursue the maximum possible charges for crimes and to enforce mandatory minimums. Sessions may care more about seeming “tough on crime” than about actually being an effective Attorney General, but it might still be worthwhile for him to revisit the open letter that twenty state prosecutors wrote to Washington State voters to explain the problems with their so-called “3 Strikes” law enacted in 1984. Since then, many more states have adopted it. Worse, the types of crime that it was originally supposed to prevent have been expanding to the point where the third strike can be as minor as petty theft – locking the culprit up for 25 years to life.

I quote the letter:

“An 18-year old high school senior pushes a classmate down to steal his Michael Jordan $150 sneakers — Strike One; he gets out of jail and shoplifts a jacket from the Bon Marché, pushing aside the clerk as he runs out of the store — Strike Two; he gets out of jail, straitens out, and nine years later gets in a fight in a bar and intentionally hits someone, breaking his nose — criminal behavior to be sure, but hardly the crime of the century, yet it is Strike Three. He is sent to prison for the rest of his life.”

These are prosecutors writing… We can’t just write this off as “fiction” or “fake news.” They, better than anyone, know that what they write is representative. Such cases still happen.

Now, as an American, do you feel comfortable with this? I hope not. And while many states are moving away from three strikes laws, those laws make up just a small fraction of the injustices within our criminal justice system.

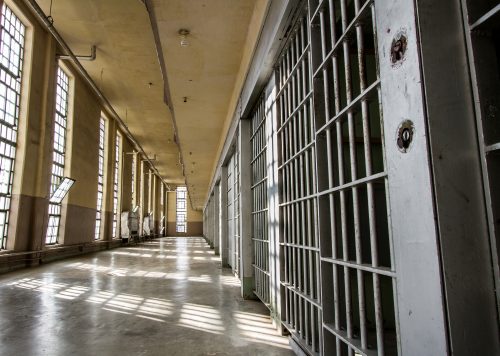

Let’s give you some data about our correctional system.

As of 2016, an estimated 6.1 million Americans are disenfranchised due to a felony conviction. This corresponds to approximately one out of every 40 voting age adults that cannot vote in our democracy owing to a current or previous felony conviction. True, rates of voting disenfranchisement vary dramatically by state and the trend is toward reduction. However, in six states – Alabama, Florida, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Virginia – more than 7 percent of the adult population is disenfranchised.

Witness the number of disenfranchised Americans over the last 56 years in figure one:

A little less than one fourth of this population is currently incarcerated, meaning that about 4.7 million adult Americans who live, work, and pay taxes in their communities are banned from voting.

Now, let’s unpack the open letter above to really feel what’s going on.

In the 1980s and 90s our government representatives decided to enact laws such as the “3-strike law” to get tough on violent and serious crime. Since then violent crime rates have gone down, but incarceration has gone up. So, what happened? Did it work?

Originally, the stiffening of laws were intended to affect felons of serious crime such as murder, rape, burglary with assault. Unfortunately, over time, the laws have been expanded to include less serious crime and even petty theft, particularly for strike three. Moreover, since more and more delinquents were incarcerated and that the correctional duration tended to expand, incarceration costs rose. Further, since incarceration was increasingly long, the inmate population over 60, who tend to have more health issues, exacerbated an already over-burdened system. In the state of California, a 25-year sentence costs the state $1.1 million. A life sentence, assuming incarceration at age 43 (the average third-strike commitment age) and death at 82 (the average life expectancy for a male alive at 43) costs $1.8 million, excluding higher medical costs of older prisoners.

To address this trend, as usual, ideology trumped common sense (let alone humanity). In the late 90s our government representatives began to privatize to improve the efficiency of our correctional system. So from the year 2000 to the end of 2009 the use of private prisons increased by 120% for federal inmates and 33% for the states, even though the overall US prison population increased by only 16%.

Did this free-market magic work? Not as we traditionally understand free markets. To begin with, private prison corporations, or PPCs, have only one client: the government. Not much free market competition here… Where can growth of profits come from? Either from a reduction of costs, or from increasing the number of “clients” — inmates. And where does a substantial portion of PPC profits go for further growth? No surprise here either: to support, sponsor, or even draft model legislation such as “three-strikes,” “truth-in-sentencing,” and “immigration-enforcement” laws that do very little to reduce serious crime but an awful lot to increase the number of “clients” for incarceration (the list of studies supporting this contention abound).

Since 2000, through their Political Action Committees (PACs) and their own employees, PPCs have given over 6 million dollars to state politicians and almost a million to federal politicians to further the status quo. (Thank you “Citizens United”!). And this does not account for lobbying expenses and the revolving-door of correctional system managers and government appointments.

So, just to recap, we have a private prison industry with a significant financial interest in incarcerating as many Americans as possible and the funds to lobby legislators for stricter sentencing laws, paired with an Attorney General (with ties to that same industry) openly dedicated to locking up as many offenders as possible for as long as possible. Despite a widespread, bipartisan consensus that criminal justice reform is absolutely essential, we’ve allowed millions of Americans to become trapped in a cycle of incarceration and disenfranchisement. This isn’t anything new, but unless we stand up to Sessions and the expansion of the private prison industry, things are going to get much, much worse.