The top tax rate wealthy Americans pay on their investment gains today runs barely half the top rate the rest of us pay on our wages. But that only begins to tell the story of how lightly taxed our richest have become compared to the rest of us.

On the surface, the nominal tax rate on long-term capital gains from investments seems somewhat progressive, even given the reality that this rate sits lower than the tax rate on ordinary income. Single taxpayers with $48,350 or less in taxable income face a zero capital gains tax rate. Taxpayers with over $533,400 in taxable income, meanwhile, face a 23.8 percent tax on their capital gains, a rate that includes a 3.8-percent net investment income tax.

But these numbers shroud the real picture. In reality, we tax the ultra-rich on their investment gains less, not more. The rates we see on paper only apply to gains taxpayers register in the year they sell their investments. But we get a totally different story when we calculate the effective annual tax rate for long-held investments, especially for America’s wealthiest who sit in that nominal 23.8 percent bracket.

For members of America’s top echelon — the wealthiest 2 percent or so of American households — the effective annual tax rate on capital gains income, the rate that really matters in measuring the impact a tax has on wealth accumulation, actually rates as sharply regressive.

That sound complicated? Let’s just do the simple math.

The federal tax on capital gains doesn’t apply until the investment giving rise to those gains gets sold, be that sale comes two years after purchase or twenty. During the time a wealthy American holds an asset, the untaxed gains compound, free of tax. In other words, as the growth in the investment’s value increases, the effective annual rate of taxation when the investment finally gets sold decreases.

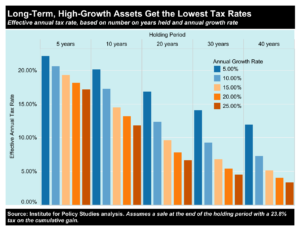

The graphic below shows how the effective annual tax rate on investment gains — all taxed nominally at 23.8 percent – varies dramatically with the rate of the gain and how long the taxpayer hangs on to the asset.

If an investor sells an asset that has averaged an annual growth of 5 percent after five years, the one-time tax of 23.8 percent on the total gain translates to an effective annual tax rate of 22.1 percent. In effect, paying tax at a 22.1-percent rate each year on investment gains that accrue at a 5-percent rate would leave the investor with about the same sum after five years as only paying a tax — of 23.8 percent — upon the investment’s sale.

In that sale situation, the tax-free compounding of gains over the five years causes a modest reduction in the effective annual tax rate, less than two percentage points. The 22.1-percent effective rate reduces the 5-percent pre-tax growth rate of the asset to a 3.9-percent rate after tax.

Let’s now compare that situation to an investment that grows at an average annual rate of 25 percent before its sale 40 years later. In this scenario, the tax-free compounding significantly reduces the effective annual tax rate to a meager 3.39 percent. That translates to a barely noticeable reduction in that 25 percent annual pre-tax rate of growth to 24.15 percent after tax.

Put simply, in our current tax system, the more profitable an investment proves to be, the lower the effective tax on the gains that investment generates. You could not design a more regressive tax system.

Who benefits from our regressive tax system for capital gains? We hear a lot from our politicians about some of those folks, the ones they want us to focus on.

Think of someone who starts a small business — with a modest investment of, say $100,000 — that over three decades grows into a not-so-small business worth $25 million. Our culture celebrates small-business success stories like that, and political leaders in both parties seek to protect the owners of these businesses at tax time. Why punish, these lawmakers ask, small business people who started from humble beginnings and sacrificed weekends and vacations to build up their enterprises?

But do we get sound policy when we base our tax rates on high incomes on the assumption that certain high-earners have sacrificed nobly for their earnings? Think of a highly specialized surgeon who made huge personal sacrifices to develop the skills she now uses to save the lives of her patients. Should the annual income tax rate she pays on her wages be ten times the effective annual income tax rate on the gain that the founder of a telephone solicitation call center realizes when he sells the business after 30 years?

We hear similar policy justifications for the ultra-light taxation of the gain realized upon the sale of a family’s farmland. But those who push these justifications rarely point out that the gain has little to do with the family’s decades of farming and far more to do with the land either sitting atop a recently discovered mineral deposit or sitting in the path of a major new suburban development.

Just as magicians get their audiences to focus on the left hand and pay no attention to the right, defenders of the lax tax treatment of investment gains heartily hail the hard work of farmers and small business owners, a neat move that diverts our attention from what simply can be windfall investment gains.

Those lucky farmers and business owners, you see, provide political cover for America’s billionaires, by far the biggest beneficiaries of the regressive taxation of capital gains. Consider Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon. His original investment in Amazon over 30 years ago, in the neighborhood of $250,000, has now grown close to $200 billion. And that’s after he’s sold off billions of dollars worth of shares. Or how about Warren Buffett, whose original investment in Berkshire Hathaway, the source of virtually all his wealth, dates back to 1962?

Bezos and Buffett, when they sell shares of their stock, face effective annual rates of tax similar to those in that far right bar of the graphic above, under 4 percent.

Buffett and Bezos may be poster children for reforming our absurdly regressive capital gains tax policy. But the problem remains wider than a handful of billionaires who founded wildly successful businesses.

In 2022, for example, the top one-tenth of the top 1 percent of American taxpayers reported nearly one-half the total long-term capital gains of all American taxpayers. Average taxpayers in that ultra-exclusive group of just 154,000 tax-return filers had over $4.7 million of capital gains qualifying for preferential tax treatment, a sum that rates some 943 times the capital gains reported, on average, by taxpayers in the bottom 99.9 percent of America’s population. And this bottom 99.9 percent, remember, includes the bottom nine-tenths of the top 1 percent, who themselves boast some pretty healthy incomes,

The regressive taxation of capital gains drives the tax avoidance strategy I call Buy–Hold for Decades–Sell. The essence of this simple strategy: buy investments that will have sustained periods of growth, hold them for several decades, then sell.

The strategy works fantastically well if you happen to hit a home run with an investment and achieve sustained annual growth of 20 percent a year, like those who purchased shares in Microsoft in 1986 did. But you only need to do modestly well to benefit enormously from Buy–Hold for Decades–Sell. If, for instance, you only manage 10 percent a year growth, barely more than the average return on the S&P 500, your effective annual tax rate if you sell at the end of 30 years would be just 9.28 percent, leaving you with an after-tax pile of cash over 13 times the amount of your original investment.

If we dig into the data produced by economists Edward Fox and Zachary Liscow, we can see clearly that once we get to the upper levels of America’s economic pyramid, the tax avoidance benefit of Buy–Hold for Decades–Sell increases mightily as we progress to the pinnacle.

Fox and Liscow estimate, for the period between 1989 and 2022, the average annual growth in unrealized taxpayer gains at various levels in our economic pyramid [see their research paper’s second appendix table]. The clear pattern: The higher your ranking in our economic pyramid, the greater your average annual growth in unrealized gains.

And when the growth in unrealized gains is running at its highest rate, the annual effective rate of tax on those gains — when finally realized — is running at its lowest. Why? The same factors that drive the growth rate of unrealized gains higher — longer asset holding periods and higher rates of appreciation in value — also drive the annual effective tax rate lower, as the graphic above vividly shows.

In short, thanks to Buy–Hold for Decades–Sell, America’s taxation of capital gains runs regressive where it most needs to be progressive — to halt the concentration of our country’s wealth. The higher we go on our wealth ladder, from the highly affluent to the rich to the ultra-rich, the lower the rate of tax. The upshot: The richer you happen to be, the smaller the portion of your investment gains you pay in tax and the greater the portion of those investment gains converted to permanent wealth. That’s how wealth concentrates.

Unless we reform the taxation of capital gains to shut down Buy–Hold for Decades–Sell, the concentration of our country’s wealth at the top — and the associated threat to our democracy — will worsen.

It’s just math.

Check below for the first six installments in this “Buy-Hold for Decades-Sell” series.

Heard About Buy – Borrow – Die? Meet Buy – Hold for Decades – Sell

Buy – Hold for Decades – Sell!

What Income Tax Rate Are Rich investors Really Paying on Their Capital Gains?

‘Wherewithal to Pay’: Deconstructing the Canard That Perpetuates Our Worst Tax Loophole

The Harsh Unfairness of ‘Buy – Hold for Decades – Sell’

‘Oppressive Taxation’ That Isn’t